By Kristine Johnson

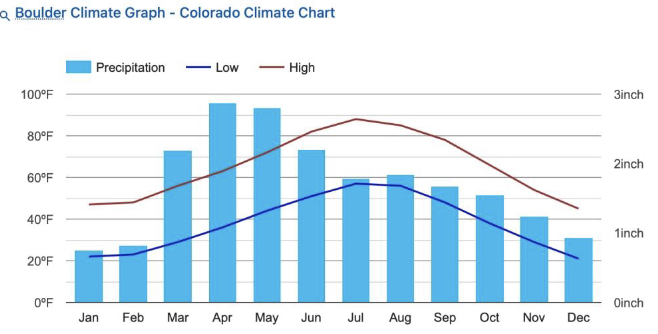

The Front Range is the dry boundary of the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains. In Boulder, Colorado, where I live, we receive about 20 inches (51 cm) of precipitation per year, peaking in late Spring. One problem with gardening in this relatively arid environment is that many Colorado residents moved here from somewhere else, usually somewhere wetter and greener. Because culture and sentiment drive landscape choices, they often want to replicate that here, whether it’s appropriate in terms of our resources or not. (I grew up in western Colorado, with half the precipitation of Boulder, so my view is that this place is absolutely lush.) As a result, a lot of Colorado urban landscapes do not reflect our water realities, and it can be hard to find support for choices in tune with nature and regeneration, though climate change and our increasingly severe droughts are changing that.

When my family made a lot of our landscaping choices twenty years ago, we were smart enough to know that lawns are for playing on, and we kept our lawn to the backyard only, where the kids were. [Side note: the kids are grown, and that lawn is now being removed.] Irrigated turf can be a legitimately good choice when it serves a purpose: space for kids and pets to play on and defensible space near structures in high fire risk areas are great reasons to have it. We did some drip emitters to support low water plant choices outside of the lawn, but I would describe drip as not the best choice for me. When watering happens automatically, people just use more water. When watering happens by hand, less water gets used; people will not water when plants and weather indicate it’s not needed. (Research backs this up.) Drip emitters made me lazy and allowed plants to get watered whether they needed it or not. Drip emitters also need maintenance; leaks waste water. I hate checking and maintaining them. For me, a better choice is low water native plants that I water by hand to get established and then which need little to no water thereafter. (I hand water trees regularly because of the climate and climate change, and I hand water my landscape when it has been a long time since any precipitation.)

My best watering choice for getting plants watered with low effort and automatically has been to learn how to harvest precipitation and garden for the rain. Last summer and fall, my family and I surfaced four of our downspouts and redirected them to basins or lower areas protected by small berms. We carved some of these spaces out of the disappearing lawn. We calculated our roof area and the volume of precipitation in typical storms and how many gallons the roof would yield and how many gallons these basins could hold. We then planted them with native plants and mulched them well. The mulch helps the infiltration of the water, and these areas will stay moist longer than the rest of the soil. We are having to do some hand watering in the heat of summer this “summer of no precipitation” (in Boulder), but otherwise, little hand watering will happen in the future. This is the best of all worlds: it requires observation and tweaking to maintain, but it’s less overall than drip or other irrigation. Water gets directed to plants which need it. We use much less water overall.

At the top of each basin is a tree or shrub which benefits from being able to draw from the basin without being at the bottom of it. The two basins in the backyard include a red osier dogwood (Cornus sericea) in one and serviceberries (Amelanchier alnifolia) in the other. In the front, we have a downspout that redirects to a basin for a large spruce (Picea of unknown species; planted before our time). Another downspout is being redirected for a basin on the north side of our house where there is an aspen (Populus tremuloides), golden currants (Ribes aureum), and raspberries (Rubus idaeus), while the final downspout to still be diverted will go to our river birches (Betula occidentalis).

If you are curious about rainwater harvesting, or rain gardening, I have a few suggestions. The first is to read Brad Lancaster’s books (Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond, Volumes 1 and 2). [A previous WOFR article reviewed Brad’s work.]

The second and most obvious is to encourage you to go out in the rain and watch your downspouts and how the water moves in your yard. I discovered that all of my downspouts, which had been attached to buried flexipipes, were completely full of roots, backing up, and spurting water very close to the house and foundation during storms of any size. (A strong admonition from Lancaster and in the training I received certifying me as a precipitation harvesting designer is to NEVER bury downspouts.) The final idea is to experiment yourself. Start small: redirect a downspout and see where it goes. Shape the earth by moving a bit of soil and see what happens. Use tools in Google Earth to calculate the area of your roof to think about your potential harvest.

Lancaster has several resources on his website specific to our region, including:

- One page place assessments

- Multi-use plant lists for water harvesting landscapes (Note: many of the plants listed for the Rocky Mountain region are not native, and are intended for permaculture applications, but one can get a feel for which native plants to substitute based on water need.)

In Colorado, we are behind our friends and family in the other Four Corners states in terms of precipitation harvesting and keeping our rain and snow on site, where it can benefit our landscapes and lessen our reliance on surface water. We all need to stop sending our precipitation to the storm sewer and start using it to water our landscapes wherever possible.