Primary Author: Deb Lebow Aal

One of the biggest challenges we face as native plant gardeners is how to design a garden with native plants. After all, we are challenging the norm. We are not planting the default landscape of an expanse of turf with a few bushes around the foundation of the house, and a tree or two. You can choose to “wildscape,” planting a prairie, but if you don’t like the wildness of a prairie in your own yard, you have many other choices. It is entirely possible to have an ordered or formal native plant garden. Just know how the plants you want to use behave in a landscape. Some stay put. Some seed around. Many native plants eventually go where they want to go – so you can start with a design, and then see where these plants want to be. Regardless of the plants you’re using, a formal design will require more maintenance. You will be editing out lots of plants.

Ignore all of this if you want the untamed, undesigned prairie look – that’s a whole different approach. But if you’re wanting a more designed and intentional look, here is a way to approach the design process. It can be easy to get overwhelmed. You can always call in a landscape design professional or start slowly with a small piece of your landscape. But here are some tips to consider before you actually put pen to paper (or put finger to keyboard).

ASSESS YOUR SITE

First, look very closely at your site. Is it sunny, hilly, tiny? Do you need room for dogs to run? Check out our piece on thinking through your landscaping goals. If you have a completely shady area, it is going to be a bit more challenging, but still doable. You are not going to want to pick plants that require full sun and hope they do well. They will not.

Focus on your paths – because that’s how most people will experience your garden. Put them where they really want to be, where they make sense.

ASSESS YOUR SOIL

You are going to want to match your plants to your soil, and not fix your soil to fit a plant. It is very, very difficult to change your soil. If it is clay, then find native plants that like clay. If it is rocky, it probably has good drainage. If you have your soil assessed (see CSU extension info on selecting an analytical lab), you will know a lot about your soil. Many gardeners (and soil labs!) get into the habit of always adding compost. Compost can do a lot of things, but over-amendment is becoming more of a recognized issue. It’s one of the top diagnoses that soil testing labs make for garden soils. The target organic matter for plants that appreciate it is 3-5% (compare that to the 50/50 topsoil/compost mixes you can buy out there). But native plants in general like lean soil and many tolerate poor drainage. So, maybe don’t worry too much about it. I know that statement is a bit controversial. It goes back to matching your plants to your site, though–pick your plants based on the site conditions they will experience. It’s a lot easier than trying to execute geological changes!

DECIDE WHAT LOOK YOU WANT

If just starting out, get a sense of different “looks and feels” of native gardens in your area before deciding. I suggest looking at the Wild Ones Front Range demo gardens*; the Chatfield and Denver Botanic Gardens, and the many other public native plant gardens in your area.

THINK ABOUT AREAS WHERE YOU WILL NOT IRRIGATE

Of course, when establishing plants, they will need water. But think about designing an area where you will not be irrigating at all long-term. This area can be your gravel mulch area, or your desert plants area. See Kenton Seth’s design for inspiration (Kenton can be found at http://www.paintbrushgardens.com/).

START SMALL

Select an area to start with. Unless you are hiring a professional, or have a lot of time, energy, and experience, it is always a good idea to bite off manageable pieces. Have an overall idea of what you want to do, i.e., a plan for the whole area, but then start small. You may find that you had a good idea that doesn’t work that well in reality, and it would be good if that “good idea” goes away before you spend a lot of time and money on it. Good places to consider starting with include areas of the lawn or garden that are difficult to irrigate, including corners, slopes, narrow strips, or irregularly shaped areas.

SELECT A LIMITED PALETTE OF PLANTS

Make a list of all the native plants you think you like (or know you like), and then whittle that down. Again, if you don’t want a wild look, you’re better off with fewer species. A good rule of thumb to start with is 10 -15 different species of plants, depending on how large your area is. You’re going to want multiples of those species, planted together in swaths and then, perhaps repeat the pattern, for a consistent and harmonious look. In selecting your plant palette, consider including diverse plant types – trees, shrubs, flowering plants (forbs) and grasses.

USE TREES AND SHRUBS AS THE BACKBONE

If you have existing trees and shrubs, think about leaving them, and designing around them. These are your longest-living plants, and often, if native, the most important for the ecosystem. Don’t try to fight them – use them to your advantage. If you do not have existing trees and shrubs, these should be designed in first. They will be your tallest plants and your visual backdrop. They may shade out a large area of your yard, so plan accordingly. The trees and shrubs provide the ‘backbone’ of your landscape. Also remember that established trees that have gotten used to water from a lawn will need water after you plant your native plants, or you will quickly have that full-sun garden you were daydreaming about.

THINK LONG -TERM MAINTENANCE

This is especially important when thinking about what type of mulch you will use. It’s generally not a good idea to put pea gravel mulch under a large tree, for example. That tree will drop many leaves and will require some work to clean up. If you have wood mulch under the tree, the leaves will just add to the wood mulch.

It’s a good idea to have an area where you “chop and drop,” e.g., where your spent plant material can just be cut up and dropped in a convenient location instead of having to haul the yard waste long distances. It does seem a bit odd to haul away dead plant material to a compost area only to haul it back much later as mulch. You can cut grasses back in 4-inch pieces, and drop them around the plants as living mulch (apparently larger pieces blow away more easily than the smaller pieces). You also may want to adjust your plant palette to lower-maintenance plants. I know folks who don’t like ornamental grasses in their landscape, because they have to be cut back in the spring (although many say don’t cut!). You may want native plants that re-seed prolifically or avoid those as requiring too much maintenance. Or avoid plants like Helianthus maximiliani, our native sunflower, that not only seeds itself prolifically, but gets very tall, and sprawls rather “interestingly,” or some might say, messily, begging to be cut back. I know, some love that look… I’m just saying think about it.

DESIGN BY SEASON AND BUILD IN DIVERSITY

Design for a succession of blooms – plant a spring bloomer next to a summer bloomer next to a fall bloomer, for an “organized” look, and so that you have something colorful and good for pollinators at all times during the growing season. So, rather than out in the wild, where there will be a gaillardia next to penstemon, next to a mullein, etc.; for a less wild look, you will have multiples of Eriogonum umbellatum (sulphur buckwheat) and Pulsatilla patens (pasque flower) for a spring bloom), next to multiples of Penstemon strictus (Rocky mountain penstemon) and Berlandia lyrata (chocolate flower) for an early summer bloom, next to multiples of Solidago (Goldenrod) and asters for late summer early fall blooms, for example. You may want to have a wide array of bloom color, or instead to have a more consistent color palette—say, just purple and yellow. Consider also having diversity of foliage color and textures—mix silvery and bluish foliage with greens for variety when plants aren’t blooming. And incorporate different foliage textures— the fine texture of grasses and small leaves with coarser foliage. Think about how your garden will look in winter. Many native plants have winter interest—evergreen foliage or berries or sculptural stems— that can liven up the winter landscape.

DESIGN BY DRIFTS

Plant clumps, swaths, or concentrations of the same plants together, to attract pollinators and make it easier for them to do their thing.

DESIGN FOR SIGHTLINES

As a general rule, group taller and beefier plants toward the back of the garden so that your medium and smaller plants are visible in front. If there is a plant you particularly love, give it a featured spot where it can grab the spotlight.

DEFINE YOUR SPACE

And lastly, for a neat and designed look, define the space. A hard border— river rocks, flagstone or bricks— always makes a planting area look neater.

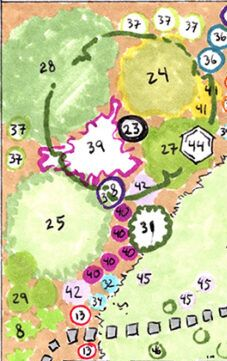

And now, design away! There are many design templates online that can give you a start. Check out the Denver/Front Range Residential Native Design created by Kenton Seth for Wild Ones and the designs included in the Low Water Native Plants for Colorado Gardens booklets. Just remember that if your purpose as a gardener is to support your ecosystem, center insect, pollinator and wildlife benefits in your design and balance aesthetics with ecosystem services. And work with mother nature, not against her – she usually wins.

- Wild Ones Front Range Chapter has two demonstration gardens: Greenverein, at 16th and Clarkson, in Denver, is a very large parkway strip that is a very good example of what you can do with a minimally irrigated tough landscape. Ekar native plant garden is a more traditional landscape, also with reduced irrigation, at Ekar Farm, 6825 E. Alameda Ave., Denver. And, not officially a demo garden for WOFR, but Depot Prairie Park, 601 W. Dartmouth Ave., Denver, has a vast array of native plants, a good place to see how these plants look.

Curious to learn more about transforming your garden into a habitat with Colorado native wildflowers, grasses, shrubs, and trees? Check out our native gardening toolkit, register for an upcoming event, subscribe to our newsletter, and/or become a member – if you’re not one already!