By Kristine Johnson with assistance and photos from Theodore Johnson Mencimer

Why Install a Rain Garden

Last year, I wrote about the “why” of rainwater harvesting, and Pam Sherman reviewed Brad Lancaster’s well-known books on rainwater harvesting. Brad is very much the “how.” I also mentioned rain gardening in my article on multi-stem trees–which should entice you with habitat plants (the “what”) which might benefit from the extra water a rain garden can provide. I have promoted composting (and leaf mold) and the native plant garden, which are an essential component of rain gardens; they absorb and store precipitation (in my webinars last winter and in this article). So if all of this has you thinking about rain gardening, what are your next steps for actually making a rain garden in Colorado? I’m going to break this down into what that might look like from an individual level, using my own garden as an example, and next steps for us as a region and as a state–look for that in a future newsletter.

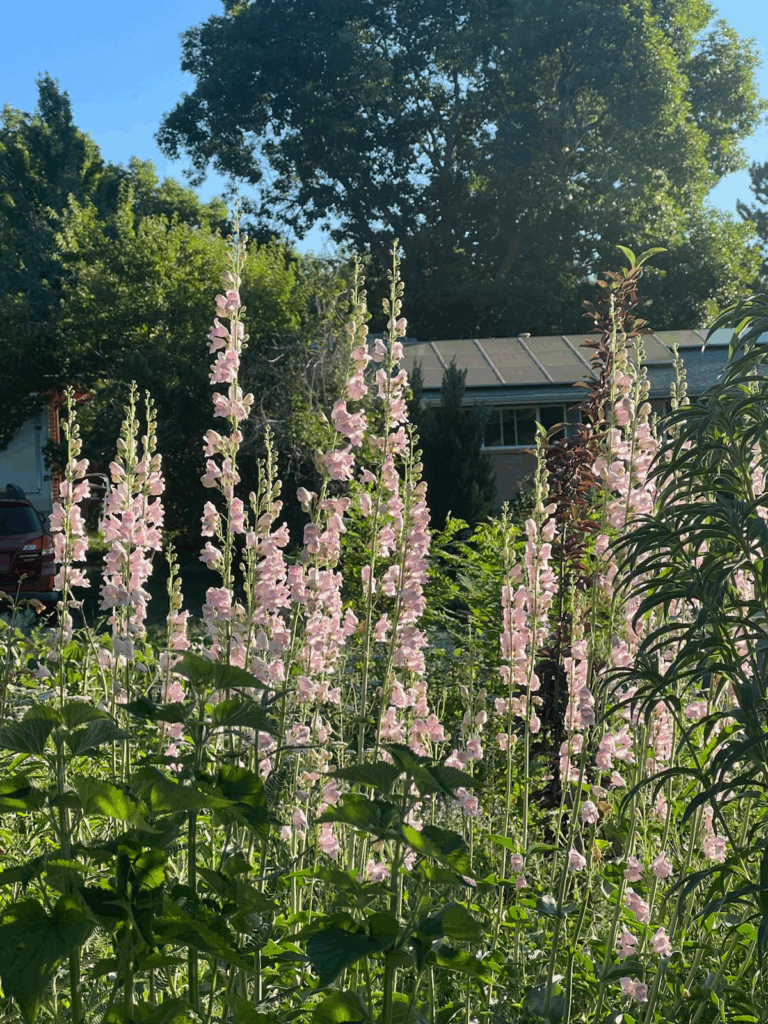

Why is rain gardening critical on an individual level? One reason is that it allows us to more easily support a wider range of beneficial plants. Many of the species featured in the native multi-stem article are among the most crucial in our region for supporting insects, birds and other wildlife. However, many are also riparian species, which means they are typically found along streams or in moister areas. They benefit from more regular water or increased moisture in the soil. If you’re interested in planting riparian habitat keystone plants, consider incorporating them into a rain garden, which can give them that extra water without increasing your irrigation.

Learning

I completed a weeklong precipitation harvesting certification course in Tucson in 2023. Last fall, I returned to audit the course again, peppering the instructors (including Brad Lancaster) with my accumulated questions, while my son, a new landscape architect specializing in native plant gardens, completed his own certification. Colorado is several decades behind Arizona and other arid regions that prioritize water conservation; Arizona is the cutting edge. Our lag is due in part to stringent Colorado water laws and the tendency of people here to focus on water storage solutions like barrels and cisterns, which can be costly and fussy and are subject to strict legal regulations. While Phoenix and its rockscapes exacerbate urban heat, Tucson stands as a beacon of novel water conservation practices centered on supporting more trees, native plants, and absorbent landscapes. I urge you to think like a Tucsonian. Use their resources and techniques, adapted for here.

My Rain Garden Projects (Or How I Installed my Rain Gardens)

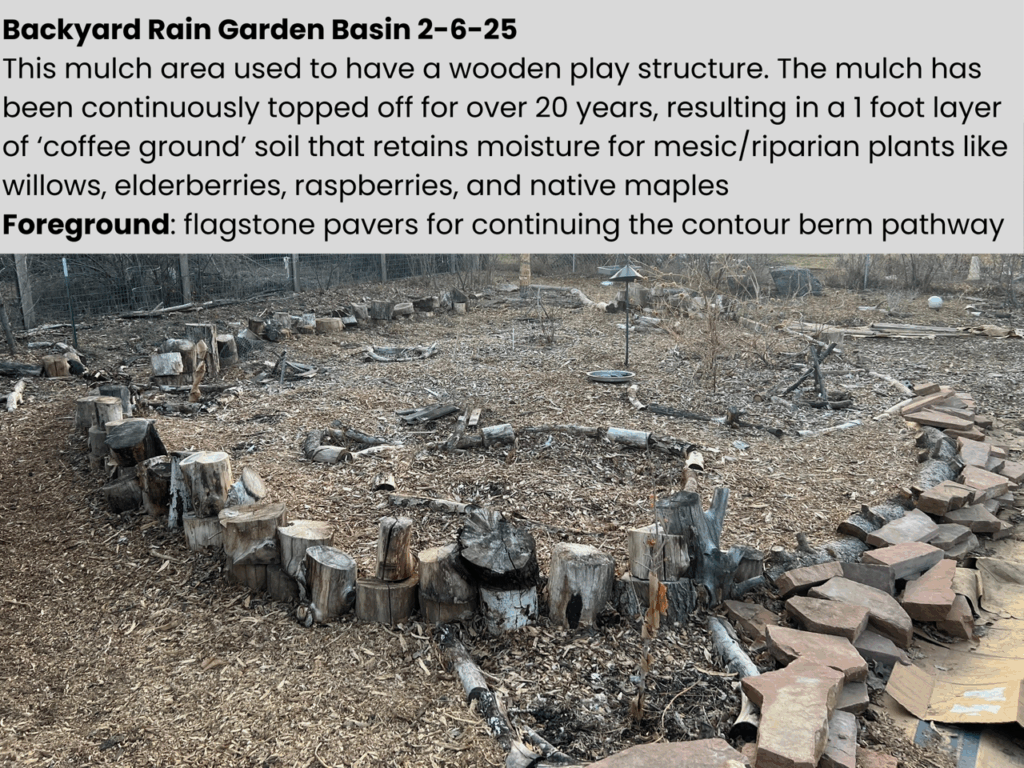

At home, our most intriguing rain garden project is the former location of the kids’ swingset. In 2004, when Theo, my eldest, was three, we excavated a large circular area to a depth of 12 inches and filled it with arborist mulch. We constructed a swingset and securely anchored it atop the mulch, ensuring no broken arms. As the mulch decomposed over the years, we annually topped it off. A few years ago, we donated the swingset through freecycle, as our children are now in college or the workforce. Because of our rain gardening, the “soil” in this rain garden is essentially 12 inches of moist, organic material resembling coffee grounds. It serves as our largest rain garden. We’ve planted a diverse range of plants that wouldn’t thrive without the substantial sponge they live in. Among them are several cutleaf coneflowers, two riverbank grapes, a hops vine, a blue willow, a couple of raspberries, rocky mountain irises, prairie cordgrass, two elderberries, a thin-leafed alder, blue vervain, swamp milkweed, bee balm, ironweed, and more.

Remarkably, this rain garden has received almost no supplemental water, yet the soil remains consistently moist. Every drop of rain that falls into this bed is absorbed. These plants thrive in soil with higher organic matter content and more readily available water. The same principle applies to my two mature river birches, which have deep leaf mulching around them to retain moisture while allowing air to reach their roots. Despite being in the lowest tier for services from our water utility, our yard is surprisingly lush and teeming with birds and insects.

Another home example: Our patio is composed of pavers that slope gently to a swale just south of the patio. We’ve planted a variety of native grasses in the swale, including June grass, big blue stem, little blue stem, switch grass, prairie dropseed, and Indian grass. There’s a decent layer of arborist mulch and compost in the swale; probably 6” at the bottom. While these grasses don’t necessarily require extra water, they’re thriving in the environment. On the other side of the swale, with blazing southern exposure, is a garden bed that is not a rain garden (it is a bit higher and doesn’t accumulate rain). There’s an inch of mulch or compost, but otherwise, it’s filled with penstemons, sages, gumweed, baby blue rabbit brush, and other xeric plants that require less water. These plants prefer well-drained soil, don’t need a lot of supplemental water, and don’t require a lot of organic matter in their soil. It’s a case of choosing the right plant for the right place. To underscore: We gave our yard ONE supplemental watering this year, in mid-August. Our soil type is a sandy loam (quick draining), and it was a hot summer.

Elements to consider in installing a rain garden

A few crucial elements must be considered when designing a rain garden, and many of these are lacking in rain gardening projects I’ve seen or read about here in Colorado. One of the most important factors is understanding and measuring the rate of infiltration of water into your soil; the size of the rain garden you can support depends on it. To determine the infiltration rate, you need to dig a hole at least a foot deep and fill it with water multiple times. Then, you should time the rate of infiltration repeatedly until you get the same rate at least twice in a row. (Why is this important? A soil with faster infiltration will absorb more water more quickly. Standing water or excess water is not great.) This video shows you how to do a percolation test.

Another important factor is calculating the area of the roof, patio, or driveway that you are draining; the size of the rain garden you can support also depends on this area. (This is super easy math!) Check out this document, or check out Appendix 3 of Brad Lancaster’s Guiding Principles for Rainwater Harvesting volume or Appendix 2 of Brad Lancaster’s Water Harvesting Earthworks volume.

It’s also important to have some familiarity with your local weather patterns and know what your typical storm size is as well as the size of a bigger storm, say a “20 year” storm. This will help you determine the volume of water you need to be able to hold in your rain garden basin in case of a large storm. (If you want to nerd out, go to NOAA’s precipitation frequency estimates and look at the tabular information, otherwise, trust me in my saying that for most of us, being able to deal with a 2” rain event gets you through most of the largest, hardest storms.)

Organic matter helps absorb and hold precipitation and will also break down over time, increasing the water holding capacity of the soil. Soil sponge, people. Rock is absolutely not an acceptable substitute and does nothing to improve drainage or absorption of water, and that’s what I see in a lot of “rain gardens” here. The only utility that rock has is for reducing erosion on steep slopes. Think of it as an “optional” feature, not a mandatory one.

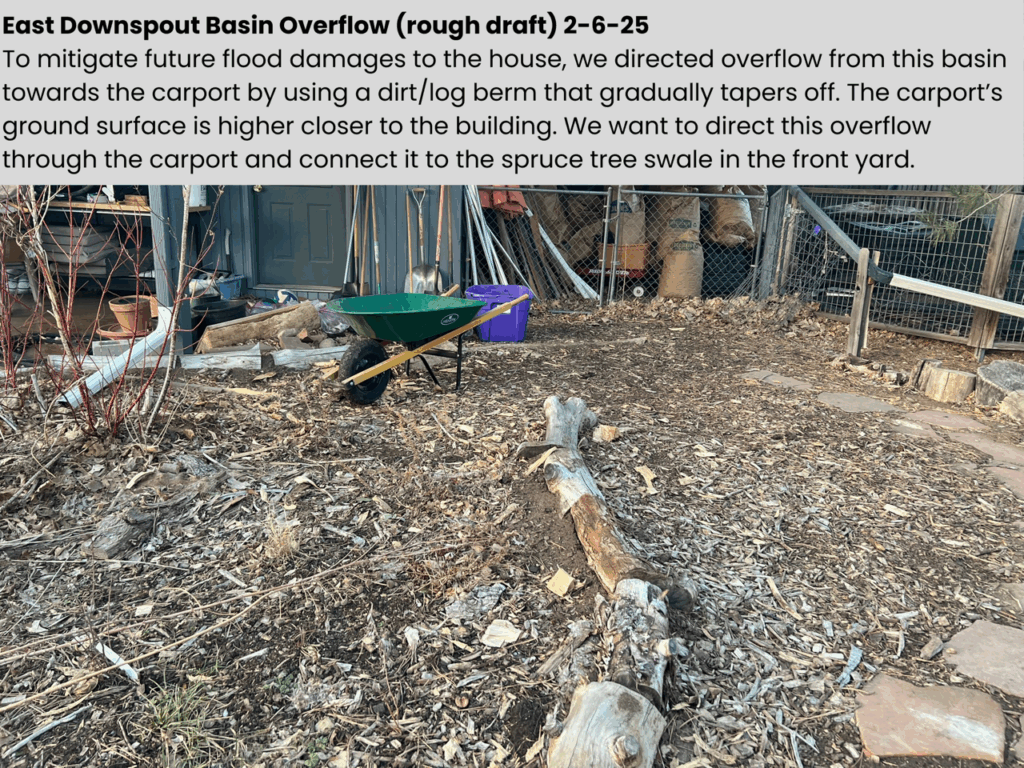

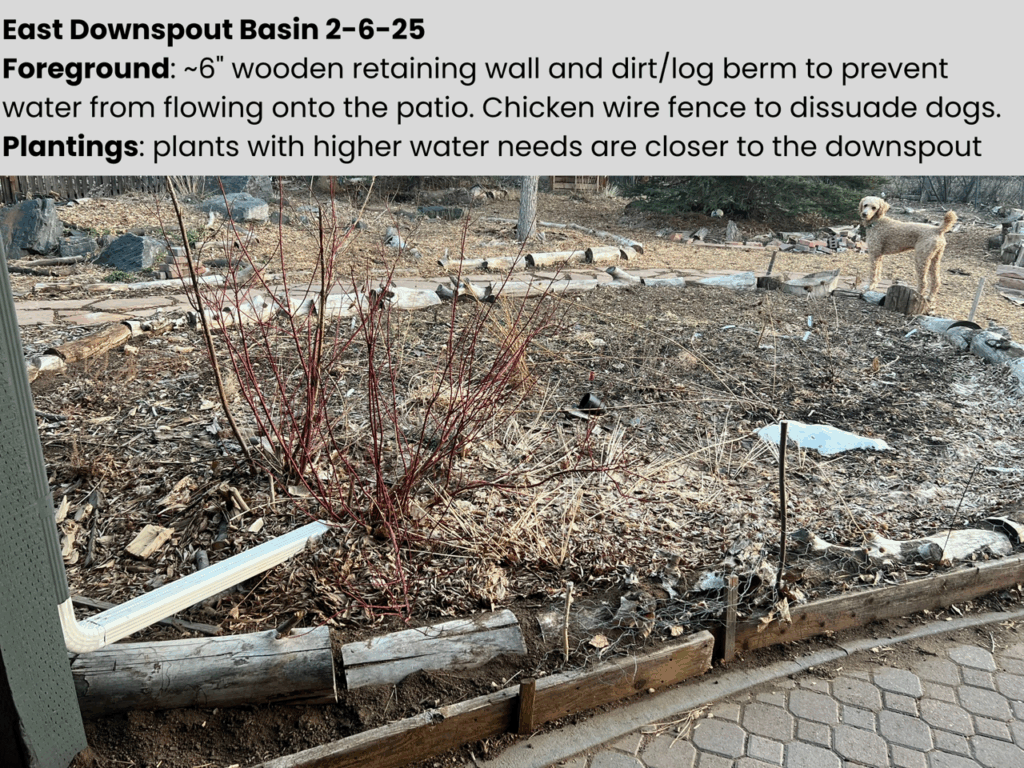

Obviously, you need to plan for where overflow from a really big storm can safely flow. (What volume does your basin hold? What amount of rain would fill it and cause it to overflow? Where are you sending that overflow?)

Finally, you need to consider the needs of the plants you want to plant in the rain garden. Riparian plants are best suited for rain garden basin bottoms, while very xeric plants are not. Since most riparian plants benefit from a consistent source of water, you may need to utilize greywater to ensure daily irrigation. Other riparian-adjacent plants can withstand dry periods and may be better suited for areas irrigated by downspouts. Again, a soil sponge (copious organic matter) also helps store soil moisture.

For More Information

Brad Lancaster’s books and many YouTube videos, as well as articles and videos at the Watershed Management Group’s website, provide excellent information on rain garden design and plant selection. (The Watershed Management Group in Tucson was where I received my certification. The certification course is currently the most comprehensive course in the U.S. and is very solid and practical.) I recommend you peruse this page at the Watershed Management Group. Information pages about several Colorado cities and their climate patterns can be found at Brad’s website. Instructions for making your own “one page assessment” for your location which incorporate a lot of the ideas above are here.