By Deborah Lebow Aal

Wait, you’re saying, there aren’t a lot of native trees on the Front Range, right? Well, most people believe that, historically, no, there were not a lot of trees on the plains of Colorado before Europeans settled here. There were Cottonwoods in the riparian areas, of course, Ponderosa pines in the sub alpine areas, and other conifers in the mountains (e.g., the gnarly beautiful Bristlecone pines). However, there is a controversial school of thought that says the Front Range was not historically plains. They argue there is proof that Native Americans manipulated a forested landscape quite a bit (See the book 1491 by Charles C. Mann). So, whether the Front Range was historically plains or forest, is an open question.

There is also the question of whether we should be populating the Front Range with trees, now. Do trees benefit the ecosystem, given the water required to maintain a tree canopy in this semi-arid part of the country? The answer is that, on balance, assuming you select trees that do not require a lot of water, trees give back to the ecosystem way more than they take. The City of Denver estimates that the 2.2 million trees in Denver provide $122 million in environmental services (e.g., soil quality improvement and nutrient cycling). In terms of cooling, they provide $6.8 million in benefits (cooling the city by 5 degrees in the summer); and $1.4 billion in stormwater services. That does not include the CO2 reduction trees provide, wildlife benefits, and the reduction in air pollutants. There are significant economic benefits as well that are not relevant here.

The bottom line appears to be that it is good to plant trees in the Front Range, preferably natives. I’ll remind you – I know if you’re reading this you know this, so I’ll keep it pithy – we need native plants to host the native insects to feed the birds. That’s it in a very oversimplified nutshell. Caterpillars are a critical food source for over 96 percent of songbirds (e.g., a pair of Carolina chickadees requires between 6,000 and 9,000 caterpillars to successfully raise just one brood of young). The power of native plants is their ability to host many more species of caterpillars than non-native plants. So, below, with many of the tree species, we will use the National Wildlife Federation’s (NWF) Native Plant Finder* to let you know how valuable these trees can be for wildlife.

It is important to have tree diversity, so please don’t pick one of these tree species and plant 20 of the same. Pick a few different trees, if you have the room, and research them well before buying (I am giving you just a snippet of information here on each tree). The present tree canopy in Denver is dominated by Maple and Ash trees, and we all probably know what’s happening to them. Denver is poised to lose something like 330,000 Ash trees due to the Emerald Ash borer in the near future. And our big maples all seem to have been planted at the same time, so they will reach the end of their life span together. We will lose yet another huge chunk of our tree canopy all at once.

So here are a few trees (some are a bit shrub like, but we’ll call them trees for now) we’d recommend:

Peachleaf Willow (Salix amygdaloides)

The king of these natives when it comes to hosting caterpillar species, this tree hosts an astounding 322 species of caterpillars!! It is the top host plant in our area. However, it’s a thirsty tree, and it likes moist, organic-rich soils. In the wild, willows are often found growing near wetland or riparian areas.

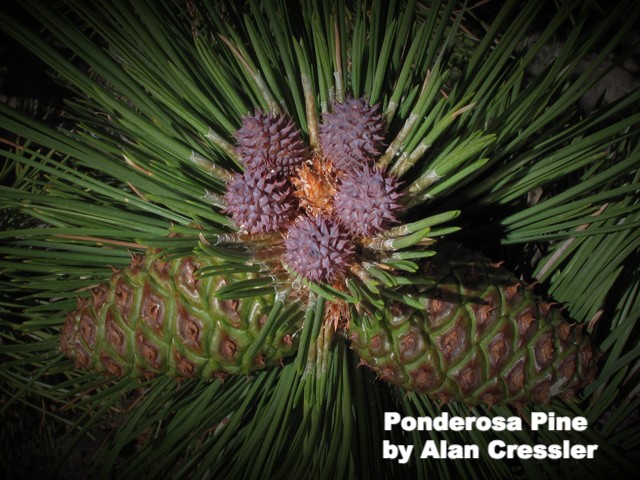

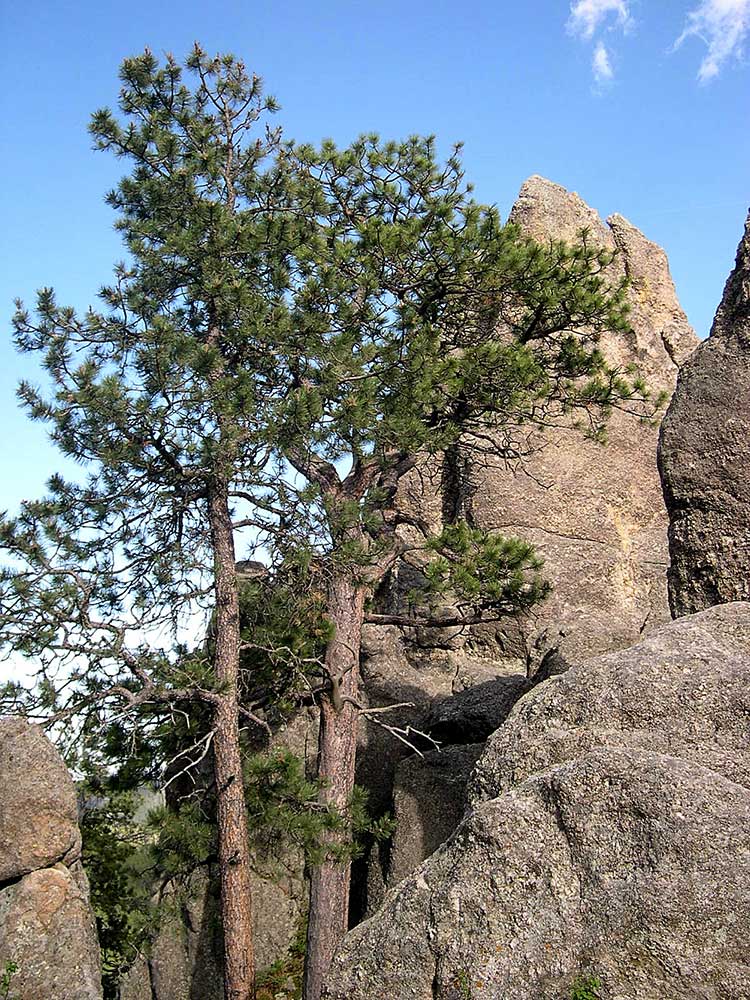

Ponderosa Pine

I think of this as the quintessential Front Range tree. It hosts 202 caterpillar species on the front range. Quite respectable. It is a very large tree, the tallest known ponderosa clocking in at 268 feet tall! I guarantee (??) that in your landscape it will not grow to be anywhere near that tall, but this tree should be reserved for large areas.

Maple, Box Elder (Acer Negundo)

A species of maple that is similar to an Ash and an elder, hence the common name of Maple ash and Box elder, it hosts 140 caterpillar species. It can grow to be 35-80 feet tall, has yellow color in the fall, and small yellow- green flowers in the spring. These trees require a bit more water than a xeriscape landscape usually provides, but can be worth it for the wildlife value.

Serviceberry: (Amelanchier alnifolia, among other native species) or Juneberry as they are commonly known

The best native tree or bush for four-season interest. I have four on a small urban lot – they do not take up much room – yet. They are gorgeous! And, they are fabulous for wildlife. The NWF native plant finder estimates this Serviceberry supports 81 caterpillar species. They have clusters of white flowers in spring, blue/black berries attractive to wildlife in the fall, and orange to red fall color.

Juniperus Scopulorum, or Rocky Mountain Juniper

Sometimes called Colorado Red Ceder, this is a medium tree, growing to 10-20 feet tall in the wild. It’s a tough tree – it can grow in dry, tough conditions, and can be found up to 8,900 feet altitude. The NWF native plant finder states that it supports 44 species of moths and caterpillars. Skyrocket juniper is a cultivar that has been overtaking the native in landscapes. Be sure to get the native, as the cultivar will not support wildlife as well.

Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana)

Chokecherry is more of an understory, small tree, that can grow to be 20-30 feet tall, and often forms thickets. It has dense clusters of white flowers in the spring followed by red fruit in the late summer. The berries are edible but extremely “puckery” ( I believe I made that word up, but you get the idea), good for jams and preserves, but the birds love them just the way they are! The berries are an important food source for wildlife in July and August.

Mountain Mahogany (Cercocarpus montanus)

These are small, slow-growing trees, reaching only 9 to 18 feet tall, but they pack a punch. They are nitrogen-fixing, meaning the roots of this tree are colonized by certain bacteria that extract nitrogen from the air and convert it into a form required for growth. Nitrogen is vital for plant success. This ability to fix nitrogen not only supports this tree, but other trees and plants around it. It also hosts 19 caterpillar species, and is very long lived. The flowers appear red when they first open, but are yellow when fully expanded. It has a rather exotic-looking growth habit. It looks very shrub-like when young, but grows to be upright and tree-like as it ages. You know it – it grows everywhere in the west, and does quite well in very dry, rocky environments.

Non-native Trees to Consider

And here are some “not quite natives” that are also recommended, because they either provide ecosystem or other benefits, for example, they are so drought tolerant that they will do well on the Front Range, and their beautiful. These were recommended by Erik Geyer, arborist at the Denver Botanic Gardens Chatfield Farms:

Russian Hawthorne (Crataegus ambigua)

Russian hawthorne is a small, beautiful, drought-tolerant tree. Its main reasons for inclusion here are that it is an extremely low water user, has an interesting habit, and gorgeous red berries in the fall. It’s a show-stopper at the Denver Botanic Gardens when those red berries come out. In 2011 Plant Select** chose Russian Hawthorne as one of their selections. These trees tend to “do their own thing” in terms of habit, in other words, they can get gnarly and can often be as wide as they are tall (12-24 feet tall, and 6-12 feet wide). They attract a wide range of flies and bees in early summer. After several frosts, the fruit turns sweet and is sought after by larger songbirds. The thorns on the tree also offer small birds and mammals protection from larger predators.

Dogwood June Snow

This is a small, skinny, but gorgeous tree. The advice we are being given now is to find species of trees that leaf out later in the spring, and this one does. Our trees are leafing out earlier and earlier in the spring, and then getting hammered by the more frequent late spring heavy snowfall we get. So, if you want your blossoms and leaves to survive, the later a tree leafs out in spring, the better. They are testing this particular dogwood at Chatfield farms, if you want to see what it looks like.

Sugar Maple Fall Fiesta (Acer saccarum FALL FIESTA)

This cultivar is also being tried out at Chatfield farms. It has been singled out as a great tree, despite not being a native, because of its vigorous and rapid growth, good resistance to heat, wind and drought, and gorgeous orange and red fall color. It’s a hardy tree, rather trouble-free, although it may need a bit more water that a xeriscape landscape would provide.

Chinkapin oak (Quercus muehkenbergii)

According to Erik Geyer (see above), “Oaks should fill the niche between natives and non-natives.” Oaks can grow really well in our environment – they seem to be well adapted to our soils. They withstand some mean storms, and are long-lived trees. Erik recommended this particular oak. It is known for its sweet and palatable acorns, which birds, and in particular hummingbirds, and other wildlife seem happy to eat.

Pinon Pine (Pinus monophylla, edulis, cembroides)

This one is not on Erik’s list, but I added it as an almost native. These are small, bushy evergreen trees, sometimes wider than they are tall. The pinon jay takes its name from the tree, with pine nuts being an important part of its diet. Pine nuts have been an important source of food for Native Americans living in the American Southwest. It is a slow-growing tree, but important for wildlife, very drought-tolerant, and seems to influence the soil in which it grows by increasing concentrations of both macronutrients and micronutrients.

As always, if you know more about any of these trees that you’d like to share, or want to add a native tree for another article on trees we will publish in the future, please email us. Pictures are also welcome!

- National Wildlife Federation Native Plant Finder, . Put your zip code in, and the site will tell you the number of butterfly and moth species that use particular native plants as host plants for their caterpillars. It’s an amazing resource! – https://www.nwf.org/NativePlantFinder/

** The Plant Select program identifies and promotes plants that are suited to gardens in the high plains and mountains of Colorado. Plants recommended as plant select are not necessarily native to our region, but are generally adapted to our conditions, and will do well in your gardens here.

Curious to learn more about transforming your garden into a habitat with Colorado native wildflowers, grasses, shrubs, and trees? Check out our native gardening toolkit, register for an upcoming event, subscribe to our newsletter, and/or become a member – if you’re not one already!