By Deb Lebow Aal

Are there things you can be doing in your landscape that make a difference – a significant difference – to climate change? Well, yes.

I first want to state that I am no scientist. I am just a layperson who wanted to know the answer to this question, and to the next question below, on assisted migration of plants. I did some research and will lay out what I found. I am very happy to hear from you if I missed something, or got something wrong.

Okay, to set the context, we all know what is predicted for Colorado climate. We are expected to get warmer and drier. We know that more severe droughts, more frequent and severe fires, conditions more suitable for insect outbreaks, and the spread of non-native species given the longer growing season, are expected. Scientists expect that there will be shifts in vegetation, e.g., from forest to shrubland, and shrubland to sagebrush. As ecosystems change, no doubt there will be winners and losers. We know that at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory in beautiful Gothic, Colorado (elevation 9,500 feet), researchers have found that the flowering season has expanded by over a month over the last 40 years, driven by earlier snow melts and a warming climate. A whole month is a big deal! It wreaks havoc, and will have complicated impacts on the ecosystem. For example, flowering plants have to compete with new plants that now overlap their blooming season, competing for pollinators and seed eaters.

The Western United States has seen a larger increase in average temperatures in the past decade than any other part of the country. Snow melt is 15-30 days earlier than 25 years ago. Spring arrives earlier, and summer is longer. Winter is milder, except for that polar vortex thing, which I’ll address shortly.

So, how does that impact gardening on the Front Range? We are going to have to deal with an arid heat that plants native to here have not had to deal with in the past. So, it remains to be seen how our garden plants will do. Most people supplement the precipitation, so perhaps many plants will do fine, but the relentless dry heat with so little precipitation is going to be a challenge. I will talk about assisted migration of plants – bringing in plants we think will do well with this new climate – but first, let’s address what we all can do to help combat climate change.

Top 10 Ways Our Landscaping Can Make a Difference

1. Limit/eliminate the use of power tools – A no brainer. The amount of fossil fuels we use to maintain our landscapes is astounding, and in my mind, unless you live in a park, unnecessary.

2. Use no synthetic fertilizers – Particularly nitrogen rich fertilizers, which require a lot of fossil fuel energy to manufacture.

3. Minimize the lawn – Lawns, particularly turf lawns, which I have written about extensively, are resource-intensive to maintain and not doing the ecosystem much good.

4. Plant woody plants, particularly trees – Trees (that will do well here with the heat and aridity1) are a fantastic way to sequester carbon, and when planted strategically, can also reduce heating and cooling costs for your home. Very important.

5. Plant native plants – Need I say more? It’s the foundation of Wild One’s mission.

6. Maximize carbon storage in the soil – Okay, I’ll say one thing about native plants: scientists say bringing back more of the short grass prairie will aid in absorbing carbon. Carbon storage in soil is one of the most important tools we have in our tool chest for combating climate chaos, and as a gardener, your part is to enrich our nutrient poor soil (enriched soil will retain water better and store more carbon).

7. Minimize soil disturbance (e.g., tilling) – Try to disturb the soil as little as possible. When adding compost and/or mulch, always top dress around your plants. It really does work. If you haven’t seen the documentary “Kiss the Ground,” I encourage you to see it. It explains no till methods much better than I ever could and will give you some much-needed hope for the future.

8. Grow long-lived perennial food sources instead of annuals – Most of our food production in the US is annuals, which is resource intensive and not sustainable. Switching to perennials makes much better sense, ecologically, especially when it comes to soil health; with their deep and extensive root systems, perennials improve soil structure and cover, and bring up more nutrients and water than annuals.

9. Reduce the urban heat island effect (reduce paved areas, utilize green roofs) –Urban areas can be as much as 10 degrees warmer than surrounding areas because of the amount of asphalt, concrete, and buildings. One way to combat that is by planting more greenery around your home, and maybe even on top of it. Yes, I am experimenting with a green roof now. I can’t tell you yet how well that will turn out (perhaps a future newsletter topic).

10. Recycle materials (both plant and building materials) – Bring in as little new material as possible. Get creative in mulching with what you have onsite or nearby in your neighborhood. Recycle whatever you can find out there. The embedded energy in concrete, in particular, is concerning.

There are many more things we can do to address climate change, but I think these are the most appropriate to our landscape. I’ve left out things like irrigation systems and composting. There’s conflicting information out there and too much to bring in here. If we, collectively, only worked on these ten points, we could make a difference. For much more information and inspiration, see a few books I’ve listed below.

What About Assisted Migration?

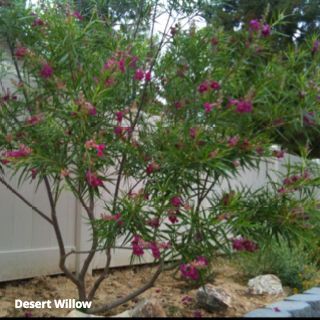

Aside from all these things we know we should do, I really wanted to know whether we should be assisting the migration of plants north, in anticipation of what will be happening with climate change. Specifically, can I plant a Desert Willow (Chilopsis linearis), because it is native to New Mexico and parts south, and hope for it to do well here? Can I call it an “almost native?” It sounds like quite a naïve question, doesn’t it? Yet it is not a simple question with a simple answer, and I wanted to know.

The short answer (and remember, I am not a scientist) is probably not. Although many plants have shifted their ranges northward in recent years, on average about 4-10 miles2 per decade, we just don’t know how wildlife will react to this change. Many conservation biologists caution that the risk of damaging ecosystems is too great, and that the chances of accidentally introducing an invasive species and doing harm, are too high. Ecologists have predicted that warming temperatures will move species northward, or to higher elevations, but the research is showing that many tree populations in the U.S. are tending to move westward, instead (not the individual tree, of course, but its progeny). The theory is that these shifts are driven more by moisture than temperature, but no one knows for sure. Research into how plants and their associated pollinators are reacting to the impacts of a warming climate is ongoing.

The other reason is the polar vortex. In short, there are two wide areas of swirling cold air above the north and south poles, kept in place by the ocean jet stream. When the jet stream starts to fluctuate, bringing warmer air to the poles, the cold polar air dips south and we get those few days of really cold, subzero temperatures. As long as that is happening, plants that can’t tolerate that cold will not do well here. So, as tempting as it is to bring plants up from parts south, they still have to deal with our cold extremes. Basic plant genetics dictate how cold of a temperature a plant can tolerate and there’s not much you can do about that.

So, bottom line is that gardeners are encouraged to “stay in their zone,” literally… their plant hardiness zone. In fact, the recommendation is for you to choose plants, especially if you’re a novice gardener, from the center of their native ranges. That is, avoid plants from the edge of a species native range. Information on a plant’s native range can be found at the USDA’s plant database website. If choosing plants from the edge of a native range, you’ll have to utilize microclimates; that is a whole article in and of itself.

What we can say here is if you want to experiment with a plant that is not quite native, don’t stray too far. Stay within a degree or two of the native, e.g. in the same genus; preferably in the same species. Don’t go looking for that South African plant to experiment with. Use your landscape as a laboratory. Think about all the roles a plant needs to play in a resilient sustainable garden, and watch it closely to see if it is playing well. Then report back. We need more backyard information.

“Pay attention. Be astonished. Tell about it.” – Mary Oliver

If you plant a desert willow, e.g., really pay attention to what insects are in its purview, and how protected it needs to be. I do have a desert willow in my yard, and so far have not seen the complicated web of life I believe it spins in New Mexico around it, but I will keep watching and reporting.

Books Recommendations

- Climate-Wise Landscaping, by Sue Reed and Ginny Stibolt – an excellent beginner book.

- The Carbon Farming Solution, by Eric Toensmeier – the best book if you want to get scientific about your carbon load and “farming” (highly technical, and not for the typical backyard gardener).

- Gaia’s Garden, by Toby Hemenway – a classic about permaculture, and the whole world of sustainable gardening.

There is also “The Climate-Friendly Gardener: A Guide to Combating Global Warming from the Ground Up” – a short online list from the Union of Concerned Scientists

Curious to learn more about transforming your garden into a habitat with Colorado native

wildflowers, grasses, shrubs, and trees? Check out our native gardening toolkit, register for an

upcoming event, subscribe to our newsletter, and/or become a member – if you’re not one already!

- Urban foresters, who view trees as vital infrastructure and as allies in the effort to mitigate the impacts of climate change are looking at selecting genotypes and species from warmer zones to the south. Planted under optimal conditions, tress live for decades, and urban foresters are selecting trees for resilience. ↩︎

- Climate-Wise Landscaping, Sue Reed and Ginny Stibolt, p.242 ↩︎